The Turks have traditionally been associated with the Arabic script, and understandibly so. For centuries Turkish was written using Arabic characters- certainly all through the Ottoman era, six centuries that left an indelible imprint on Western consciousness.

Page from the 16th century Shehname-i Selim Khan, by Seyyid Lokman, with miniature painting by Naqqash Osman.

The original alphabet of the Turks had been different; a runic script that we know from monuments still existing in central Asia, such as the 8th century "Orkhon" (Orhun) inscriptions found in the Orkhun valley in Mongolia.

Turkish writing as it used to be: the 8th century "Orkhon" (Orhun) inscriptions, Orkhon valley, Mongolia.

(Image from the media.)

The Turks adopted the Arabic script only after converting to Islam- the faith prevalent among the Turks had been Shamanism. The Turks came into contact with Islam as early as the 7th century, and their comversion spread over several centuries. (Some Turkish peoples became Christian, such as the Gagauz -also Gagaus- in the Balkans, and one large group- the Khazars- chose Judaism; 740 AD.)

Adopting the Arabic alphabet was one visible aspect of submission to the cultural influence of the Arabs, an almost inevitable outcome of conversion to their religion. In the ensuing centuries, even when the Ottoman Turks became the overlords of the Arabs, they remained culturally submissive. Arabic and also Farsi (Persian) made such inroads into the Turkish language from the court elite downwards that "Ottoman" developed into a completely different dialect reserved to the palace and the administration, essential Turkish surviving among the plain folk.

The predominant alphabet in the Islam-dominated Middle East had for centuries been, and still is, the Arabic one, with Hebrew used by the Jews (introduced into the secular sphere as the official alphabet of Israel after its founding in 1948). The Greek minority and their Orthodox church used the Greek alphabet, and the Armenians had their own. The Latin alphabet was used by the "Levantine" community- families of Western origin settled in Turkey, mostly concentrated in Istanbul's Pera district, comprising today's Galata, Karaköy- Beyoğlu area. These families were involved mainly with trade with Europe, with which they maintained strong connections, and lived a European lifestyle. They were the original clients of the famous Orient Express and when a hotel was built for the inbound passengers of the famous train, it was not built anywhere near the station, but in Pera, and was appropiately named the Pera Palace.

Cadde-yi Kebir, or la Grande Rue de Pera in the Beyoğlu (Pera) district in Ottoman times, where the Levantine community was concentrated. Note the prevalence of Latin letters. Note also the unveiled women- a priviledge of non-Muslim women, even when citizens of the Ottoman Empire. Muslim women did not share this priviledge- a direction towards which the present AKP is nudging us under the guise of "freedom to cover up".

Cadde-yi Kebir, or la Grande Rue de Pera in the Beyoğlu (Pera) district in Ottoman times, where the Levantine community was concentrated. Note the prevalence of Latin letters. Note also the unveiled women- a priviledge of non-Muslim women, even when citizens of the Ottoman Empire. Muslim women did not share this priviledge- a direction towards which the present AKP is nudging us under the guise of "freedom to cover up".

As long as the Ottoman Empire felt powerful enough to have its way, it could afford to remain aloof of what was happening in the west. In the19th century, as a series of defeats forced the Ottomans to acknowledge the growing military and technological superiority of the West, the Sultans' governments took tentative steps towards reform. Under Selim III (reigned 1789-1808) French military advisors came to retrain the army, and French was taught as a second language at military schools. French eventually became the official second language of the Ottoman Empire, used in government- particularly the foreign service.

Because of high government debts, an administration of public debts (Düyun-u Umumiye) was founded which earmarked specific sources of state revenue to the payment of debts to foreign lenders. Founded in 1889 and delving deep into Turkish-Ottoman economic life, it contributed to the prevalence of the French language and the Latin alphabet in Turkey. The treaty of Lausanne of June 24th 1923, following the Turkish War of Independence, disqualified the Public Debts Administration from directing and earmarking state revenues, empowering it only to distribute the repayments to the creditors. It was not dissolved until 1939, with the last installment of the debts paid as late as 1954.

The Ottoman Empire was defeated and partitioned after the First World War, and it is thanks to the nationalist resistance led by Mustafa Kemal (later Ataturk) that Turkey reemerged as an independent state in 1922, becoming a Republic in 1923. Mustafa Kemal became the first president of the Republic and embarked on a program of reform and modernization that included the the introduction of a new alphabet derived from the Latin alphabet (November 1st, 1928).

There was- and is- something very special and particular about the new Turkish alphabet and orthography. The alphabet was not to be used simply to transliterate the words from the Arabic alphabet, nor would it follow Western ortographical practices. Each letter would indicate one sound and one sound only, unlike, for example, the "c" in English, which is pronounced differently in "cat", "city" and "cello". There are no diphtongs, for every sound there is a letter. The Turkish "ç" replaces the English "ch" of "chew" and the "tch" of "watch". The Turkish "ş" replaces the "sh" of "show".

"X" was not adopted because of redundancy; "KS" gives exactly the same sound. (So a "taxi" is a "taksi"). "Q" has an equivalent in the Arabic alphabet (ق) as distinct from "K" (ك) but because Turkish speakers pronounce both letters as "K", and have perceived the two letters to represent the same sound, it only served to confuse, so the new Turkish alphabet made use only of the "K". As for "W", that corresponds to an Arabic letter (و), which Turks always pronounce as a "V". However, the Arabic alphabet does not have a "V". The modern Turkish alphabet adopted the "V" and dropped the "W". So the Arabic word "qahwah" ( قهوة, meaning coffee) becomes "kahve" when a Turk pronounces and writes it.

When Prime Minister Erdoğan unravelled his "democratization package" on September 30th, 2013, one of the "democratizing" ingredients turned out to be the introduction of Q, X and W into the Turkish alphabet. A mere detail of spelling being introduced in a "democratization package" may seem strange, and it is! Though they are not used in Turkish words, Q, X and W are well known and recognized by every literate person from elementary school up, even if not everybody can pronounce them. Indeed, how could we avoid using these letters in the day and age of "www" web addresses, children clamoring for "Nesquik" and portly shoppers looking for XXLarge T-shirts?

The common acceptance of the superiority of the West- shared even by the fundamentalist Islamists (Prime minister Erdoğan and cronies are always flying to the US and mullah Fethullah Gülen won't quit his Pennsylvania ranch) will facilitate this; not only are Western names and expressions senselessly popular, but even patently Turkish names are frequently used in Westernized form because they seem more chic that way.

I am not implying that the firms choosing foreign names or foreign corruptions of Turkish words have ulterior motives, only that he Turkish public is not inclined to show much resistance to the bastardization of its language if it feels it's modern and fashionable. Combined with the "freedom for the keyboards" and the new, "liberalizing" trend of returning historic names, it may not be long before we hear arguments for reverting to Smyrna for İzmir, Adrianople for Edirne, and most ominously, Constantinople, not Istanbul. We will be thus made to feel we are living in a country that isn't really ours, which may well be the intention!

Adopting the Arabic alphabet was one visible aspect of submission to the cultural influence of the Arabs, an almost inevitable outcome of conversion to their religion. In the ensuing centuries, even when the Ottoman Turks became the overlords of the Arabs, they remained culturally submissive. Arabic and also Farsi (Persian) made such inroads into the Turkish language from the court elite downwards that "Ottoman" developed into a completely different dialect reserved to the palace and the administration, essential Turkish surviving among the plain folk.

The predominant alphabet in the Islam-dominated Middle East had for centuries been, and still is, the Arabic one, with Hebrew used by the Jews (introduced into the secular sphere as the official alphabet of Israel after its founding in 1948). The Greek minority and their Orthodox church used the Greek alphabet, and the Armenians had their own. The Latin alphabet was used by the "Levantine" community- families of Western origin settled in Turkey, mostly concentrated in Istanbul's Pera district, comprising today's Galata, Karaköy- Beyoğlu area. These families were involved mainly with trade with Europe, with which they maintained strong connections, and lived a European lifestyle. They were the original clients of the famous Orient Express and when a hotel was built for the inbound passengers of the famous train, it was not built anywhere near the station, but in Pera, and was appropiately named the Pera Palace.

Cadde-yi Kebir, or la Grande Rue de Pera in the Beyoğlu (Pera) district in Ottoman times, where the Levantine community was concentrated. Note the prevalence of Latin letters. Note also the unveiled women- a priviledge of non-Muslim women, even when citizens of the Ottoman Empire. Muslim women did not share this priviledge- a direction towards which the present AKP is nudging us under the guise of "freedom to cover up".

Cadde-yi Kebir, or la Grande Rue de Pera in the Beyoğlu (Pera) district in Ottoman times, where the Levantine community was concentrated. Note the prevalence of Latin letters. Note also the unveiled women- a priviledge of non-Muslim women, even when citizens of the Ottoman Empire. Muslim women did not share this priviledge- a direction towards which the present AKP is nudging us under the guise of "freedom to cover up".As long as the Ottoman Empire felt powerful enough to have its way, it could afford to remain aloof of what was happening in the west. In the19th century, as a series of defeats forced the Ottomans to acknowledge the growing military and technological superiority of the West, the Sultans' governments took tentative steps towards reform. Under Selim III (reigned 1789-1808) French military advisors came to retrain the army, and French was taught as a second language at military schools. French eventually became the official second language of the Ottoman Empire, used in government- particularly the foreign service.

Because of high government debts, an administration of public debts (Düyun-u Umumiye) was founded which earmarked specific sources of state revenue to the payment of debts to foreign lenders. Founded in 1889 and delving deep into Turkish-Ottoman economic life, it contributed to the prevalence of the French language and the Latin alphabet in Turkey. The treaty of Lausanne of June 24th 1923, following the Turkish War of Independence, disqualified the Public Debts Administration from directing and earmarking state revenues, empowering it only to distribute the repayments to the creditors. It was not dissolved until 1939, with the last installment of the debts paid as late as 1954.

The Public Debts Administration (Düyun-u Umumiye) building,

designed by Levantine architect Alexandre Vallaury, who also designed the Pera Palace hotel mentioned in the text.

(Image from the media.)

The Administration earmaked tax revenues from tobacco to the the payment of foreign debts. Here is a share certificate of the Régie Cointèressée des Tabacs de l'Empire Ottomane.

The presence of the Latin alphabet in the nominally sovereign Ottoman Empire had a quasi-colonial aura.

The non-Muslim minority and the Levantine communities relied on schools opened and operated by foreign institutions such as Saint Benôit and Notre Dame de Sion for their children, and some less-conservative Turkish families favoured these schools for a better and more international education. The Ottoman administration founded its own elite schools, where French was part of the curriculum. One such important institution was as Mekteb-i Sultani ("Imperial School") at Galatasaray (in Pera), which continues its French-as-second-language tradition today as the Galatasaray lycée. With the writing and the language came new ideas- including revolutionary ones.

Newfangled ideas coming from Europe, such as liberté, égalité and fraternité gave birth to the Jeune Turc movement (the French apellation is used also in Turkish) which forced the reluctant monarch Abdul Hamid II (the dour-looking figure above the flags) to concede to a constitution and a parliament in 1908.

Abdul Hamid came to the throne in 1876 with a promise of a parliament, which he fulfilled, then promptly rescinded with the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish war of 1877-78. It took another thirty years to persuade him to reopen it.

On May 13th 1909, reactionary elements in the army rose against constitutional parliamentary rule, in support of the Sharia (religious law) and the the strict hand of the Sultan-Caliph. It broke out in the artillery barracks in the Taksim district.

The reactionary uprising was put down by progressive army elements (Hareket Ordusu, "The Army of Action"). The young Mustafa Kemal was an army captain among their ranks.

Sultan Abdul Hamid II was deposed and placed under house arrest in Salonica. He was replaced by the portly and avuncular Mehmed Reshad.

The barracks, the starting point of the uprising, were demolished in 1940, the area becoming a park- the famous Gezi park of the uprising in June 2013. That uprising started when the AKP government under Prime Minister Erdoğan attemptedto raze the park to build a shopping center that was to be built to resemble the demolished artillery barracks- an ideologically significant move for an administration that feeds on religious fanaticism and Ottoman nostalgia.

(See "Taksim Promenade Park", 31 May- Mayıs 2013.)

A commemorative plaque showing the new standard Turkish alphabet, as presented to Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. The plaque is on display in the museum at Ataturk's Mausoleum (Anıt Kabir) in Ankara.

Mustafa Kemal Ataturk personally introducing the new Latin-based alphabet in Kayseri,

Sept. 20th, 1928.

A schoolbook teaching the alphabet of the Republic. The cover, by İhap Hulusi Güney, "the" poster designer of Turkey at the time, shows Ataturk himself and his very dear, adopted daughter Ülkü. (Ülkü Adatepe).

There was- and is- something very special and particular about the new Turkish alphabet and orthography. The alphabet was not to be used simply to transliterate the words from the Arabic alphabet, nor would it follow Western ortographical practices. Each letter would indicate one sound and one sound only, unlike, for example, the "c" in English, which is pronounced differently in "cat", "city" and "cello". There are no diphtongs, for every sound there is a letter. The Turkish "ç" replaces the English "ch" of "chew" and the "tch" of "watch". The Turkish "ş" replaces the "sh" of "show".

"X" was not adopted because of redundancy; "KS" gives exactly the same sound. (So a "taxi" is a "taksi"). "Q" has an equivalent in the Arabic alphabet (ق) as distinct from "K" (ك) but because Turkish speakers pronounce both letters as "K", and have perceived the two letters to represent the same sound, it only served to confuse, so the new Turkish alphabet made use only of the "K". As for "W", that corresponds to an Arabic letter (و), which Turks always pronounce as a "V". However, the Arabic alphabet does not have a "V". The modern Turkish alphabet adopted the "V" and dropped the "W". So the Arabic word "qahwah" ( قهوة, meaning coffee) becomes "kahve" when a Turk pronounces and writes it.

When Prime Minister Erdoğan unravelled his "democratization package" on September 30th, 2013, one of the "democratizing" ingredients turned out to be the introduction of Q, X and W into the Turkish alphabet. A mere detail of spelling being introduced in a "democratization package" may seem strange, and it is! Though they are not used in Turkish words, Q, X and W are well known and recognized by every literate person from elementary school up, even if not everybody can pronounce them. Indeed, how could we avoid using these letters in the day and age of "www" web addresses, children clamoring for "Nesquik" and portly shoppers looking for XXLarge T-shirts?

"Freedom for the keyboards". My aging keyboard, the type that has been on sale in Turkey for years, already equipped with Q, W and X. well before the "liberating" prime minister Erdoğan came to power. It is even known as the "Q-keyboard".

There used to be a Turkish keyboard once, known as the F-keyboard, developed in the 1950's bunching the more frequently used letters in Turkish at the center. It was approved by the Inter-Ministerial Standardization Committee on September 20th 1955. In 1974 the Turkish Standards Institute (TSE, Türk Standartları Enstitüsü) made the F-keyboard mandatory in official use. With internationalization, the Q-keyboard became more and more widespread. Today, you would be hard pressed to find an F-keyboard. Note that the F-keyboard also included the Q, W and X. I wrote my master thesis in English in 1982 on my sister's already derelict F-keybard typewriter.

Cover of a DVD on sale in Turkey, purchased several years ago. The "W" of Walt Disney as well as of Winnie the Pooh have appeared with no controversy. So what was the problem?

Germany attempted a reform in orthography in 1996 ("Rechtscreibreform") which aroused some controversies but was certainly not presented as part of anything so laden with significance as a "Democratization Package".

So is it much ado about nothing? In a sense, it is, but considering the AKP's record, nothing is the way it seems. The first thing that comes to mind is the official incorporation of Kurdish orthography as step towards autonomy and eventual secession of the southeast and even the eastern provinces as an independent Kurdistan- the Prime Minister practically blessed the process in Diyarbakır on November 16th. The city and the region are still within the internationally recognized borders of the Republic of Turkey but the mayor Osman Baydemir nevertheless greeted Masoud Barzani, leader of the autonomous Kurdish region of Northern Iraq, with the words "Welcome to northern Kurdistan". I can't help remembering the indignation President De Gaulle caused when he said "Vive le Québec libre" during a state visit to Canada in 1967.

So is it much ado about nothing? In a sense, it is, but considering the AKP's record, nothing is the way it seems. The first thing that comes to mind is the official incorporation of Kurdish orthography as step towards autonomy and eventual secession of the southeast and even the eastern provinces as an independent Kurdistan- the Prime Minister practically blessed the process in Diyarbakır on November 16th. The city and the region are still within the internationally recognized borders of the Republic of Turkey but the mayor Osman Baydemir nevertheless greeted Masoud Barzani, leader of the autonomous Kurdish region of Northern Iraq, with the words "Welcome to northern Kurdistan". I can't help remembering the indignation President De Gaulle caused when he said "Vive le Québec libre" during a state visit to Canada in 1967.

Prime Minister Erdoğan with guest of honor Barzani to his right, Diyarbakır, November 16th, 2013. Barzani interestingly chose paramilitary dress.

(Image from the media.)

Like the Turks, the Arabs, and practically everybody else in the region, the Kurds used the Arabic alphabet. The Latin-based alphabet that is known as the Kurdish alphabet dates from 1932, four years after the introduction of the Latin-based Turkish alphabet mentioned above. It was developed by Djaladat Ali Bedirhan (Celadet Alî Bedirxan in Kurdish spelling) who used it in in his periodical Hawar which he published in Syria, a country that was under French mandate at the time. Apparently inspired by the Turkish precedent (note the atypical use of the letter "C" for the "G" sound as in "George", as in the Turkish alphabet), it includes the Turkish-specific "Ç" (for "ch" as in "chop", unlike French practice) and "Ş" (for "sh" as in "shop"). It does not include the Turkish "Ğ" nor does it follow the Turkish distinction between "İ" and "I". Some vowels have extra accents.

The introduction of the new letters into the official Turkish alphabet seems to open the way to a few things.

Firstly, to allow the use of "Kurdish" letters in given names, without having to transliterate them into official Turkish orthography. Just as the inventor of the alphabet chose to call himself "Bedirxan" rather than "Bedirhan".

Secondly, place names. The city of Dersim was the seat of an insurrection against the young Republic in 1937. It was put down with force. The name was changed to "Tunceli" ("Land of Bronze"), but not, as commonly believed, after the uprising, but more than a year before, in January 1936. In recent years, as a part of its vendetta against the Republic, its eagerness to discredit it's founder, Ataturk, and also within the framework of the US-backed program for carving an independent Kurdistan out of Turkey, Iraq and Iran, the AKP has dug up the Dersim insurrection and focused on the hard way it was put down, damning the administration of the time, and returning the original name.

This opened the way to the reviving of other historic names

and the introduction of the new letters means the official Turkish orthography will no longer have to be followed. This past October Aysel Tuğluk, independent MP for Van proposed her constituency be renamed "Wan". This in no way counts as a return to the original name since, as I pointed out above, the Arabic alphabet, used by the Turks and the Kurds, did not distinguish between "V" and "W", using a single letter which the Arabs pronunce "W" and the Turks "V".

Only a step away is the further alienation of names, through a progressive and programmed deterioration of Turkish orhography. When adopting the Latin alphabet for Turkish, the orthography was not imported as is, but adapted intelligently to suit the needs of the language. Thanks to the simplicity, the principle of one letter for each sound and one sound for each letter, it is the easiest writing for anybody to learn; Turkish children are able to read and write before the first semester is out.

There is a real danger of Turkish orthography being corrupted to ape what the western powers used in the weakest decades of the Ottoman Empire- and this will be done with the pretence of "returning to the original"!

The introduction of the new letters into the official Turkish alphabet seems to open the way to a few things.

Firstly, to allow the use of "Kurdish" letters in given names, without having to transliterate them into official Turkish orthography. Just as the inventor of the alphabet chose to call himself "Bedirxan" rather than "Bedirhan".

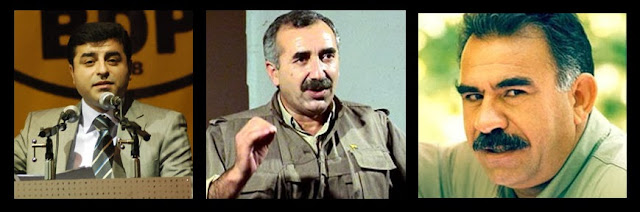

Big names of the Kurdish movement in Turkey: from left to right, Selahattin Demirtaş, MP for Diyarbakır and co-chairman of the Kurdish separatist BDP, Murat Karayılan, PKK guerilla leader, and Abdullah Öcalan, imprisoned PKK leader with whom the AKP government is negotiating.

All three leaders have Turkish surnames, "demir taş" meaning "Iron rock", "kara yılan" meaning "black snake" and most appropiately, "öc alan" meaning " one who takes revenge", which is exactly what he is doing right now with relish! (As for their names, all three are of Arabic origin!)

The surnames probably go back to the surname law of 1934, and the parties concerned might consider the surnames forced upon them, but they have not taken any steps towards changing them

The surnames probably go back to the surname law of 1934, and the parties concerned might consider the surnames forced upon them, but they have not taken any steps towards changing them

This opened the way to the reviving of other historic names

and the introduction of the new letters means the official Turkish orthography will no longer have to be followed. This past October Aysel Tuğluk, independent MP for Van proposed her constituency be renamed "Wan". This in no way counts as a return to the original name since, as I pointed out above, the Arabic alphabet, used by the Turks and the Kurds, did not distinguish between "V" and "W", using a single letter which the Arabs pronunce "W" and the Turks "V".

Only a step away is the further alienation of names, through a progressive and programmed deterioration of Turkish orhography. When adopting the Latin alphabet for Turkish, the orthography was not imported as is, but adapted intelligently to suit the needs of the language. Thanks to the simplicity, the principle of one letter for each sound and one sound for each letter, it is the easiest writing for anybody to learn; Turkish children are able to read and write before the first semester is out.

There is a real danger of Turkish orthography being corrupted to ape what the western powers used in the weakest decades of the Ottoman Empire- and this will be done with the pretence of "returning to the original"!

A horse-drawn streetcar from the Ottoman period, preserved in the Koç Museum, Istanbul.

The destination plate gives the terminal points of the route in Arabic and Latin letters. The Latin letters are used according to French ortography, the most powerful foreign influence at the time. The French spelt the Turkish names the best they could:

Béchiktache- Karakeuy

Modern Turkish ortography would have it like this:

Beşiktaş-Karaköy

(Image from the media.)

The destination plate gives the terminal points of the route in Arabic and Latin letters. The Latin letters are used according to French ortography, the most powerful foreign influence at the time. The French spelt the Turkish names the best they could:

Béchiktache- Karakeuy

Modern Turkish ortography would have it like this:

Beşiktaş-Karaköy

(Image from the media.)

Sakarya Ottoman Hotel.

The word "Ottoman" is really a corruption of "Osman", the name of the first ruler of the dynasty.

The Turkish for Ottoman is "Osmanlı", but somehow, it is often felt that the foreign corruption is more stylish than the original.

(Image from the media.)

Above:Selamlique and below: Haremlique: a chain of shops supplying stylish coffee and more. The names are the the French spellings for Haremlik and Selamlık, the male and female portions of the segregated Ottoman household.

(Images from the media.)

Cafe and Qahwah- two versions of the same word, neither in Turkish, in the Kadıköy district of Istanbul.

(Image from my own camera.)